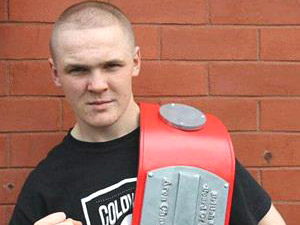

Kieran is a former UK Central Area Lightweight Champion boxer from Heywood, Greater Manchester.

As an amateur Kieran was a National Junior ABA champion, 3x National finalist, represented his country winning a Multi-Nations Gold Medal in Bydgoszcz, Poland before winning the GB 3 Nations at Flyweight.

As an amateur Kieran was a National Junior ABA champion, 3x National finalist, represented his country winning a Multi-Nations Gold Medal in Bydgoszcz, Poland before winning the GB 3 Nations at Flyweight.

Kieran also held wins over 3 times ABA champion Tommy Stubbs and Olympic bronze medalist Michael Conlan.

Kieran adopted “Vicious” as his boxing nickname and was trained by Bobby Rimmer in Manchester for his first eleven paid contests, winning eight on points and two by knockout.

He then teamed up with Irish trainer John Breen where he engaged in another four paid contests including a UK Lightweight Central Area title bout where he defeated previously unbeaten Joe Elfidh (7-0) by way of knockout in the fifth round.

Kieren was forced to retire from boxing in January 2013 after suffering damage to his brain in his fight with Anthony Crolla.

BOXING RECORD

Kieran Farrell (born 27 June 1990) is a British former professional boxer who fought at lightweight.

| Kieran Farrell | |

| Statistics | |

| Nickname(s) | Vicious |

| Weight(s) | Lightweight Super featherweight |

| Nationality | British |

| Born | 27 June 1990 (age 27) Heywood, Greater Manchester, UK |

| Stance | Orthodox |

| Boxing record | |

| Total fights | 15 |

| Wins | 14 |

| Wins by KO | 3 |

| Losses | 1 |

He was trained by Bobby Rimmer in Manchester for his first eleven professional fights, winning eight on points and two by knockout. He then teamed up with Irish trainer John Breen where he engaged in another four paid contests including a lightweight Central Area title bout where he defeated previously unbeaten joe Elfidh (7-0) by way of knockout in the fifth round.

Farrell was managed by Steve Wood for the first two years of his career by switched to Ricky Hatton‘s Hatton Promotions in the summer of 2011. After a short spell with Hatton Promotions, Kieran joined up with promoter Dave Coldwell at Coldwell Promotions.

Farrell was forced to retire from boxing in January 2013 after suffering brain damage during his fight with Anthony Crolla.

Farrell was awarded a BEM British empire medal by her majesty in the Queen’s 90th birthday honours 2016.[1

Farrell was awarded a BEM British empire medal by her majesty in the Queen’s 90th birthday honours 2016.[1

Copyright content kindly authorised by Kieran Farrell

Image credit copyright Boxingnewsonline.net

The People’s Gym Opens – 4/6/13

Vicious – A Documentary – 5/4/16

A Year On – 30/7/14

Being A Promoter – 20/12/16

Kieran On The BBC 3/11/16

Kieran Farrell: ‘I couldn’t put my socks on. Now they say I’m a miracle’

Image copyright: The Guardian ‘I’ll always love boxing. It’s still my dream. It’s still my life.’ Photograph by Christopher Thomond for The Guardian

An Interview by Donald McRae 18/3/13. View it here: https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2013/mar/18/kieran-farrell-interview-boxing-donald-mcrae

They call it a miracle,” Kieran Farrell says, his eyes opening wide as wintry sunshine streams through the lace curtains of his parents’ front room in Heywood. Tucked away in gritty anonymity, between Bury and Rochdale, Farrell has lived his whole life in Heywood. Yet last December, just over three months ago, the 22-year-old nearly died after a brutal battle.

Farrell and Anthony Crolla produced one of the fights of the year as their struggle for the English lightweight title went the distance in Manchester. Crolla got the verdict and Farrell, who still believes he should have won the fight, sank slowly to the canvas and into an oblivion which skirted death.

He somehow survived the terrible bleeding on his brain. Farrell will never box again but, now, the stain on his unbeaten record, in his 15th professional contest, seems to hurt almost as much as the loss of 30% of his brain. Yet, as the bite of a hard winter raises goosebumps on his pale flesh, the damaged young boxer grins helplessly. He recalls seeing a similar expression cross his doctor’s face last week.

“The neurosurgeon was smiling,” Farrell says. “Dr Hewitt said: ‘Kieran, it’s a miracle. I’ve got results from the latest MRI scan and it’s astonishing. Your brain looks 100% normal.’ The 30% which died can’t ever come back. But he showed me the scan. ‘Look,’ he said as he pointed to my brain, ‘no shadows. There’s not even scar tissue.'”

Farrell shakes his shaven head gently, as if not wanting to rattle his fragile brain. “It’s mad. When I first came home, after hospital, I couldn’t even put my socks on. I’d been this amazingly fit boxer and I ended up like that. I used to cry over my socks every morning. But they now say I’m a walking miracle.

“On the night of the Crolla fight they thought I could die. When you’re getting punched in the head and your brain is bleeding it’s very bad. Dr Hewitt showed me the scan from that night. There was a ridiculous amount of blood on the brain. He told me it was only a small gash on the brain. But the brain was soaked in blood. They had to wait weeks to see if the blood would disperse and it did. It’s incredible I’m here talking to you.

“But I’m still a bit hopeless with short-term memory. I’ll say to Nathan [his brother] ‘What day is it today?’ He’ll tell me. A little later, I’ll ask again. Nathan says: ‘You just asked me, you numpty!’ But everyone is so happy I’m alive.”

The boxer explains what happened to him that dark December night. “I was suffering from an acute subdural hematoma – as big as they get. Dr Lamb was in the ambulance and he said it was a miracle I made it to the hospital. They said my survival came down to my elite level of fitness. Even when I was training for four-rounders I’d run eight miles. I was building to my goal of becoming a world champion.

“It was still touch and go. When they carried me away on a stretcher someone said I was applauding the fans singing my name. I wasn’t. My hands were fitting. I was gone. My mum was in the ambulance and I can only imagine how hard that was for her– to see her little boy, gone, and fitting. When I eventually came round, five days later, I said: ‘Dad, I just wanted to be world champion.’ My dad, Brian, he’s a big man, but he started crying. I was crying too. It was like Lassie had gone missing again.”

Farrell laughs, and it’s easy to join him. Boxing’s gravity, however, cannot be avoided – and Farrell makes a telling point about how extreme dehydration nearly killed him. If anything can be gleaned from his experience, apart from insight into his warmth and bravery, as well as the compassion of his doctors and family, it centres on the outrageous risks boxers take to make weight. When the brain is denied fluid it has even less protection against heavy blows. Neurosurgeons have compared the impact to a brain rolling around an empty box – the equivalent of a dehydrated skull.

“The night before the fight I weighed 9st 8lb,” Farrell remembers. “I hardly ate or drank the week before. Everyone says drink as much water as you want. But if I drank 500ml I’d put on a pound and need to sweat it out. Every morning I was on the treadmill and there was a portable sauna in my bedroom. I’d go in there with my sweatsuit so I kept my water levels low. I didn’t have a wee until the morning after I weighed-in. As soon as I stepped off the scales I had all these sports rehydration drinks and cups of sweet tea. I was downing water like a sponge. I could feel my body sucking up the moisture. By the time I walked to the ring I weighed 10st 12lb. I’d put on 18 pounds.”

Farrell shows me a letter Dr Hewitt wrote about him in January. Its contents meant the end of something he loved almost as much as his family – boxing. Amid the medical terminology and details of Farrell’s score on the Glasgow Coma Scale, measuring the depth of unconsciousness, Hewitt writes movingly.

“I do not give this advice lightly because I understand that his career has been very promising and, of course, he has a lot of talent and has worked very hard to get the achievements that he has to date,” Hewitt suggests when stressing that Farrell should never box again. He then issues a stark warning. “To resume boxing would carry a very significant risk – an acute subdural hematoma can be life-threatening.”

“The doctor likes boxing but he knows it’s very dangerous,” Farrell sighs. “He says it’s over for me.”

He cries less now but, when we met for the first time last month, Farrell admitted that he often retreated to his room so he could let his tears fall. “My whole life was boxing,” he said.

I’d been struck by his haunting admission that he watched his fight against Crolla repeatedly. “I’ll be sat on my bed and Nathan says: ‘What are you watching?’ I say: “I’ve got the Crolla-Farrell fight on.'”

Today, Farrell fires up his iPad on his parents’ sofa. We see Crolla enter the ring. “I’ve watched it 20 times at least,” he murmurs. “But I’ve only reached the end once. I saw my legs collapse. It’s not nice.”

The packed Bowlers Arena in Trafford Park makes a raucous setting. As he watches Crolla duck through the ropes I ask Farrell how often he has heard from his opponent since their tragic fight. “Anthony called me when I got out of hospital and he’s rung me again. He needed to hear I was OK. We all know how hard it was for Chris Eubank after he sent Michael Watson into a coma. But, since the amateur days, Anthony was my friend. Then, for five weeks before we fought, he wasn’t my friend. Now the fight is over we’re friends again.”

Farrell’s eyes are misty as he stares at the screen. “This is a moment I’ll never forget. I’m coming out to So You Want To Be A Boxer from Bugsy Malone. I got chills down my spine. Look at the kids stretching their hands out. See how I slap their hands with my gloves? See how happy I look?” His hands are shaking and I hold the iPad instead. “I’ve still got the chills now. It was supposed to be my coming-out night. If I’d beaten Crolla I’ve have been on my way.”

The opening rounds slide past in a blur as, with ferocious work-rate and combinations, Farrell edges ahead. “He tucked up well,” Farrell says of Crolla, “and it was hard to get through his defence. But it makes me proud. I watch it as a fight fan now. It was a Fight of the Year candidate and so I enjoy it.”

As we enter round six, Farrell says, distressingly: “It now felt like there was water on my brain. The swelling was growing.” His right hand touches his head tenderly as he remembers wincing even when his cornermen toweled him down between rounds. Punches to the head became a searing agony. “The doctor couldn’t believe I kept going those last four rounds with severe bleeding on the brain. But I wanted to win.”

The commentary frames our deepening silence. “What these kids have gone through over nine rounds,” a commentator says. “You can see Farrell gritting his teeth.”

“Farrell’s at an early stage of his career and he stepped up to take this fight,” his co-commentator agrees. “It shows his character.”

Julie Farrell, Kieran’s mother, arrives with bags of shopping. We pause the recording just before the 10th and, in the kitchen, she tells me how, at this stage of the contest, she went outside for a breather. “I thought he was all right. I heard everyone chanting Kieran’s name. I couldn’t believe that we’d end up in the back of an ambulance.”

She smiles. “But look at him now …”

We glance at the couch. Farrell is ready for the last round. I sit down again, next to him. “I’ll watch it all the way through this time,” he says.

At the final bell, as the crowd roars, the commentator sounds as moved as he is enthused. “Absolutely amazing,” he cries. “Absolutely brilliant. What a fight. Credit to both boxers. Take a bow, gentlemen.”

Darkness soon descends. “That’s when I started feeling dizzy,” Farrell says as his trainer, John Breen, lifts him into the air in apparent celebration.

“That’s my legs going,” Farrell says as he crumples to the canvas. “It’s funny. I could hear everyone singing: ‘There’s only one Kieran Farrell …’ Even Crolla’s fans joined in.”

We watch him disappear into the tunnel of unconsciousness. The commentator sounds worried: “Kieran Farrell is in a little bit of trouble.”

Later in the afternoon, with Farrell calm and cheerful, we walk up Wham Street, where he lives, and head towards his different life at the top of the road. “I wanted to open my own steak house,” Farrell chortles, “but I don’t have the financial backing for that. But I’ve got my own gym now on Wham Street.”

It’s a strange name for a street – “Just like the group,” Farrell said when he spelt out Wham – but it seems fitting for a fighter. The wham-bam-bam-bam of fists smacking into heavy bags and speed balls will soon echo from the old printing factory which Kieran and his brother Nathan, and some generous friends, are converting into a gym. His new dream is to turn himself into a great trainer: “I’ll never box again, but I can teach others. I hear the kids walking past on their way home from school. They say: “That’s Kieran Farrell’s gym. I’m going there.”

Inside, with a new ceiling in place, the converted gym is taking shape. It has the evocative atmosphere for a place of boxing dreams – even if it will cost a lot and need the boost of his benefit dinner next month which he promises will feel more like a celebration of his short career than a funeral.

Farrell’s face shines with pride as he takes me on a tour of the building. “I’ll call it Farrell’s Gym or Farrell’s Amateur Boxing Club. But, outside, we’re going to have a huge sign saying Viva Les Vicious.”

He is gentle and kind; and it amuses us both that he always called himself Kieran ‘Vicious’ Farrell. The vicious old business of boxing nearly ended his life. But here, on a winter afternoon on Wham Street, it sustains him still. “I’ll always love boxing,” Farrell says. “It’s still my dream. It’s still my life.”